Revisiting “Philadelphia’s Sick Politics”

As legal battles continue re the 2020 Presidential Election, considerable attention is being paid to Pennsylvania, and to the Democrat stronghold of Philadelphia, specifically. The city’s legendary reputation for political chicanery has predictably been a topic of conversation. It may be tempting to view the conventional wisdom of Philly as a cesspool of corruption through a typical, partisan left-right lens (i.e., Republicans viewing the city more critically than their Democrat counterparts), but this isn’t necessarily the case. This 2013 Philadelphia Inquirer column (“Philadelphia is so corrupt that exposing corruption in the newspaper is kind of worthless”) and this 2017 VICE piece (“Is Philadelphia the Most Corrupt City in America?”) are helpful, as is this 2020 Philadelphia Magazine article (“The Utterly Ridiculous History of Lawbreaking [and Allegedly Lawbreaking] Philly Politicians”), to make my point (also see this 2011 column in the Inquirer by progressive Will Bunch). Of course, adversarial openly partisan/ideological pieces are not hard to find (see, e.g., here and here for just two among many recent efforts). Political corruption in the city is so endemic that a few years ago locally-based freelance journalist Aaron Kase explained Philadelphians “are hardly shocked when another scandal breaks”. In my invited 2005 Inquirer op-ed, titled by the paper “Philadelphia’s Sick Politics”, I argued some city residents take “a bizarre, macho pride” embracing the corrupt status quo.

With all of this in mind, I’d like to use former U.S. Representative Bob Brady – described in June 2020 by Philadelphia Magazine as “a true Philly political boss if there ever was one” – as an example to non-Philadelphians in an effort to explain why city residents (and alums) have essentially become resigned to corruption.

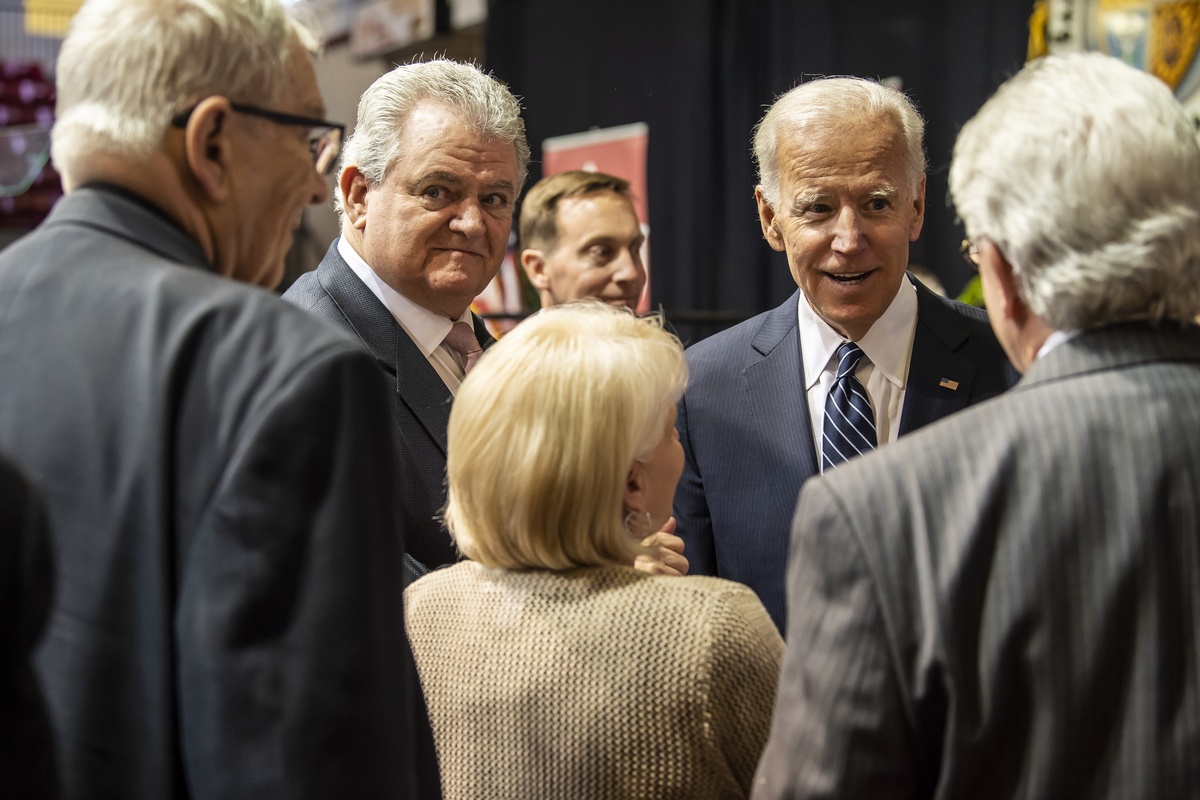

Then-Vice President Joe Biden with then-Congressman Bob Brady in 2015

Bob Brady

Books can be written on Bob Brady’s fascinating political career, so keeping this to basics – even for such a limited exercise – will be challenging. As a 2017 Philadelphia Magazine profile says, “In New York City, Tammany Hall is something children learn about in history class. In Chicago, Richard J. Daley has been dead more than 40 years. In Philadelphia, Bob Brady’s Democratic machine reigns supreme” (as of 2017, Democrats outnumbered Republicans 7 to 1). Brady got his start in Philly politics in the mid-1970s with then-City Council President George Schwartz as his mentor. When Schwartz went to prison in the early 1980s for his role in ABSCAM, Schwartz picked Brady to succeed him. Brady was the head of Philadelphia’s Democratic Party a short five years later. When Congressman Tom Foglietta was tapped by President Clinton to be Ambassador to Italy in 1997, Philadelphia’s ward leaders chose Brady to fill the seat.1 Brady went on to win the general election and entered Congress in 1998, where he remained until he chose not to run for re-election in 2018. A Washington Post headline on his departure reads, “Philadelphia Democrat Robert Brady, dogged by scandal, will retire from Congress.” The referenced “scandal” involved a $90,000 payoff scheme among Brady’s campaign operatives to a 2012 Democrat primary challenger for him to exit the race. Though multiple witnesses implicated him in the conspiracy, and while others including Brady’s longtime strategist Ken Smukler were convicted (a U.S. District Judge said what Smukler did “really subverts the election process”), Brady was never charged. According to Roll Call, “Brady eluded prosecution…after litigators allowed the statute of limitations of his alleged crimes from 2012 and 2013 to expire.” Incredibly (but predictably, if you know anything about Philly), Smukler made news in October 2020 when he appeared on a Zoom call with Brady and dozens of ward leaders to discuss their get-out-the-vote strategy for the upcoming elections. He had successfully served a year of his 18-month prison sentence and was thus available. Reflecting back on the 2017 Philly Mag profile mentioned above given what has transpired since, consider this excerpt:

Ken Smukler, Brady’s top political operative, is nodding vigorously as Brady gives his full-throated defense of the Democratic machine. “Remember when we sat at the restaurant in the Bellevue with all Obama’s field people?” Smukler asks. “And one of them says, ‘Well, who do we have to talk to to get more provisional ballots into a poll location?’ I say, ‘You’re talking to him!’ That’s why I’ve always said: People don’t realize the uniqueness of a big-city party machine.”

Brady (left) and Biden (right) speak with guests at a St. Joseph’s University event in 2018

On November 7, 2020, Politico featured longtime Biden ally Brady, Philadelphia’s Democratic Party Chairman, in a piece detailing the election’s hectic aftermath among Biden’s closest confidantes. Interestingly, a 2018 Inquirer article discussed a Biden visit to raise funds for Brady, potentially to assist a 2022 U.S. Senate bid to oust Pat Toomey. At the time, Brady explained he hoped Biden, his friend of 30 years, would run for President in 2020, “I’ll be with him every step of the way.” Brady of course later became a Biden delegate, and tweeted the following after media outlets called the 2020 election:

Philadelphia delivered the White House to @JoeBiden https://t.co/3byvMV7nk8

— Congressman Bob Brady (@BobBradyPHL) November 8, 2020

I chose to highlight Biden’s “dear friend” Brady because he became a small part of my research agenda on organized and white-collar crime back in the early 2000s. I was then completing a decade-long project examining Philly’s murderous Black Mafia along with the notorious syndicate’s political networks. No Black Mafia leader has exemplified political influence more than Shamsud-din Ali. Before I explain how this relates to Bob Brady and Philadelphia’s corrupt culture, a primer on Shamsud-din and the Black Mafia is necessary.

Shamsud-din Ali and Philadelphia’s Black Mafia

Philadelphia’s self-named Black Mafia was formed in the 1960s, originally focused on the extortion of illicit entrepreneurs (i.e., those persons who could not turn to law enforcement, such as drug dealers, pimps, bookmakers, and bar owners who housed such activities). By the early 1970s, the syndicate had vastly expanded its territory and its enterprises. Extortion targets now included legal businesses, the group commandeered entire sections of the city’s narcotics trade and gambling action, and they were involved in numerous (often sophisticated) financial crimes. Along with their substantial political ties, most of their success was predicated on brutal, public acts of violence – of competitors and especially of witnesses. The group is responsible for some of the city’s most infamous crimes. Indeed, some of their murders garnered national attention (e.g., the 1972 slaying of drug wholesaler “Fat Ty” Palmer and four others in Atlantic City’s famous Club Harlem as Billy Paul performed on stage; the largest mass murder in Washington, DC history in 1973 when a Black Mafia hit squad killed several Hanafi Muslims – including drowning a nine-day-old baby – in a home donated by basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; and the 1973 Cherry Hill, NJ slayings of hustler, onetime Camden mayoral candidate – and close Muhammad Ali friend – Major Coxson and his common-law wife). As a result of the group’s unrelenting violence, two Black Mafia leaders were placed on the FBI’s “Most Wanted” List in late 1973.2

Unbelievably, and – for this essay’s purpose – importantly, all throughout the mob’s mayhem of the 1960s and early 1970s, the syndicate was exploiting local and federal funding initiatives designed to curb urban violence and to enhance “community development”. The public support of prominent politicians was exploited by the murderous syndicate in various ways. It is understandable extortion targets were intimidated still further, and that the community was left anxious and confused at best (this was also true regarding Black Mafia members’ close ties to celebrities like Muhammad Ali). The Black Mafia formally incorporated no less than three “community action agencies”, most infamous among them the outrageous Black Brothers, Inc. (please see note 1 below). These remarkable circumstances resulted in several Black Mafia members developing significant political ties, including Shamsud-din Ali.

Shamsud-din Ali, who took over Philadelphia’s notorious Nation of Islam Temple 12 in 1976 following the demotion of the NOI’s influential and feared Jeremiah Shabazz, was a Black Mafia leader formerly known as Clarence Fowler. Fowler (who was a captain in the paramilitary Fruit of Islam under Shabazz at the time) was convicted of a 1970 murder and served a few years in prison before his conviction was overturned by a divided Pennsylvania Supreme Court (a re-trial was ruled out by officials when the key witness against him refused to participate after being visited by Black Mafia henchmen). Just prior to his imprisonment for murder, Fowler headed the North Philadelphia office of a federally-funded “anti-gang” initiative operated by District Attorney Arlen Specter. While in Philly’s corrupted Holmesburg Prison, Fowler was an influential figure inside the institution and on the street; he returned to society as Shamsud-din Ali.

Immediately following his 1976 release from prison, Drug Enforcement Administration informants described Shamsud-din continuing the Black Mafia extortion racket, with tributes being paid to his mosque. He was also discussed on FBI wiretaps by prominent Black Mafia drug dealers in the 1980s. Authorities learned from sources that Shamsud-din maintained his influence in the prison system and had arrangements with labor leaders to employ convicts who would be in his debt as part of early release programs. Shamsud-din was not charged throughout these years, and his stature on the street and in urban politics rose considerably. Concerning the latter, by 1996 a leading political reporter wrote, “Anyone who wants to seek political office in this town should first seek Shamsud — that is the word among potential candidates.” His networking and get-out-the-vote prowess was widely acknowledged, and he became a force in the city’s Democrat circles.3

In the late 1990s Shamsud-din Ali became the subject of a massive federal narcotics investigation when wholesalers for a drug-dealing rap group (with Black Mafia origins) named RAM Squad discussed his alleged role on wiretaps. That probe involved an overheard conversation of Shamsud-din asking a drug wholesaler for $5,000, explaining he needed the money to give to a longtime aide to Philadelphia Mayor John Street. The revelation spawned a separate and distinct investigation into municipal corruption that involved “pay-to-play” shakedowns and “no-show” jobs (including Shamsud-din’s politically-related businesses); it was discovered Shamsud-din was a major power broker in municipal contracting and his stature was acknowledged by politicians and by violent entrepreneurs, alike. Concerning the latter, Dawud Bey (son of founding Black Mafia member Roosevelt “Spooks” Fitzgerald) was recorded complaining to another prominent drug dealer that Shamsud-din was “walking with kings and we’re out here hustling.”4 Bey was likely referring to Shamsud-din’s prominence in city politics, which included things like meeting President Bill Clinton during a visit with Mayor Street. One of the FBI’s recorded conversations involved Shamsud-din boasting about young heavily-armed drug dealers fearing him, no doubt because of the Black Mafia’s legendary reputation on the street. As I chronicled years ago:

Ali was recorded telling “business consultant” Joseph Moderski: “When I see these guys clinging to me like that, then I know that the friendship between the mayor and I … these guys are aware of it … They aren’t gonna alienate me at all, see.” He was equally proud of his reputation on the street, telling Moderski that some people “don’t think that I’m altogether civilized … and believe me, in our community, in the African-American community, nobody takes me lightly. The guy that’s in the back alley with two … nine millimeters on his hips don’t take me lightly.”

The drug investigation led to the convictions and/or guilty pleas of 37 people, and the corruption probe resulted in another 20 persons pleading guilty or being convicted at trial, including the City Treasurer. In 2005, Shamsud-din was convicted of 22 counts of various racketeering and fraud charges and was sentenced to seven years and three months in prison; he was released from federal prison in December 2013.

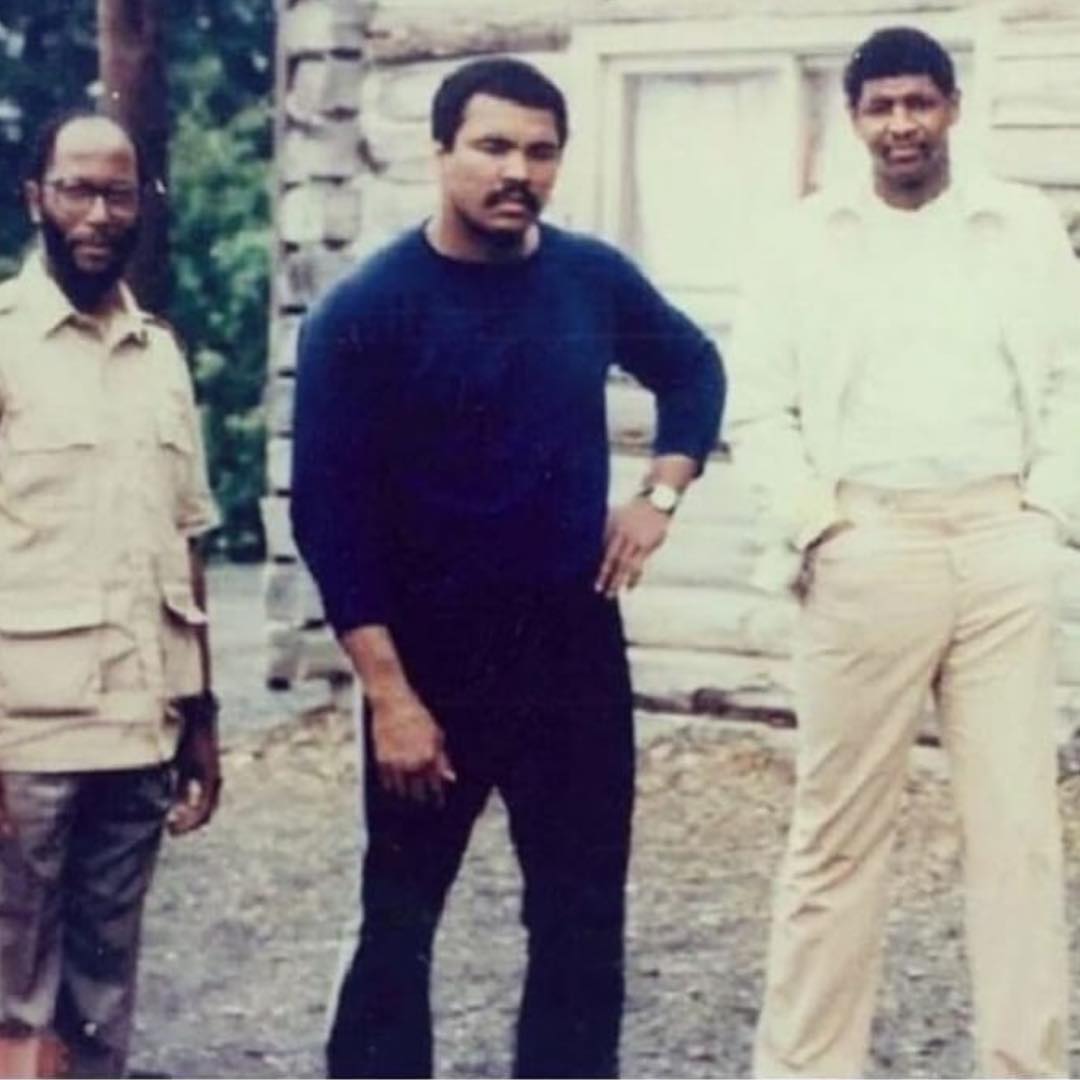

Above is a classic photo of Shamsud-din Ali (left) next to boxing legend, Muhammad Ali, who is flanked by another Philadelphia Black Mafia leader named Robert “Nudie” Mims. Mims, also known as Ameen Jabbar, died in prison in 2012 while serving a life sentence for his role in one of the city’s most infamous crimes. In 1971, Mims and some of his Black Mafia confederates robbed DuBrow’s Furniture Store in South Philly, killing one employee and setting many others on fire. (The robbery/murder/arson is discussed @12:45 in the 2007 BET American Gangster episode,“Philly Black Mafia: ‘Do for Self’.”) The above photo was likely taken while Mims was briefly out of prison following the May 1980 PA State Supreme Court granting of a retrial. Mims would soon be re-arrested after police executed a search warrant and discovered cocaine, a Thompson machine gun, an Israeli Army Uzi submachine gun, strainers, scales, and other drug-related equipment in his apartment. When back in prison, Mims was crucial to major heroin deals in the Philadelphia area, working with Black Mafia and Italian-American organized crime figures.

Okay, so you have a brief sense of Philadelphia’s Black Mafia and of Shamsud-din Ali, and you’re already aware the city’s notorious reputation for political corruption is well-earned. Why, then, my choices of Shamsud-din Ali and Bob Brady?

Philadelphia’s Offensive Corrupt Political Culture

The above photograph of Shamsud-din Ali and Bob Brady was posted online April 18, 2019 by Shamsud-din’s wife, Faridah, who captioned the photo thusly: “Lifetime friend congressman Bob Brady, congratulating my husband, Shamsud-din for his many outstanding accomplishments and contributions to society.“

Before she met Shamsud-din, Rita Spicer lived with Earl “Mustafa” Stewart, a largescale drug dealer. She left Stewart in 1990, just months before he was arrested and admitted to delivering hundreds of kilos of cocaine to the Junior Black Mafia (the ill-fated, short-lived attempt replicating its far more consequential predecessor). During her time with Stewart (aka Earl Dixon), Spicer was a government informer providing information against the dealers competing with the JBM. She married Shamsud-din Ali in the summer of 1990, and adopted the name Faridah. Her son, Azeem Spicer, was convicted nine years later for a firearms offense in a case in which he was cleared of attempted murder. In January 2001, police responded to a late-night alarm call at an apartment above Shamsud-din Ali’s office. They found $30,000 worth of marijuana and cocaine, scales, 5000 baggies, and a Tech-9 semi-automatic pistol in the apartment, and arrested its resident, twenty-eight-year-old Azeem.

He was held for trial on drug and weapon charges, but the D.A.’s Office dropped the weapon charge before the case went to trial. In court, Faridah Ali testified that rap groups also used the apartment, because she and Azeem ran a music production business together. A jury acquitted Azeem Spicer on the drug charges after renowned mob attorney Joseph Santaguida argued that others had access to the apartment and that the narcotics did not belong to his client.

Revisiting the massive 2003 corruption probe above which began with Shamsud-din Ali, among those convicted was Faridah Ali along with their son, Azeem (“Osh”), and their daughter, Lakiha (“Kiki”), who were each found guilty for their respective roles in a “ghost teacher” scam.5 When she was charged, Faridah Ali told the press, “I’m being targeted because I’m Muslim. I’m African-American. I’m woman.” She was also charged as part of Shamsud-din’s vast racketeering enterprise. As I wrote in 2007:

Faridah Ali, Shamsud-din Ali’s wife and co-defendant, had her case severed and pleaded no contest to most of the federal racketeering, fraud and tax charges on September 26, 2005. At her February 2006 sentencing hearing, however, Ali admitted she was guilty of defrauding Community College of Philadelphia, a Mercedes-Benz dealership, and a bank. She also admitted to wire fraud, tax evasion, and filing false tax returns. Long removed from the days of professing her innocence, saying she was being investigated because she was African-American, and calling the probe “an attack on Islam,” Faridah now matter-of-factly told the court, “I’m saying it publicly. I broke the law.”

As the government argued in the sentencing memo for Faridah Ali, “Under the guise of performing community service, the Ali family, instead, lined their pockets with funds earmarked to help poor people of the West Philadelphia area, who they purported to serve.”

The public learned that Faridah, just like Shamsud-din, was involved with her own enterprises involving or requiring political support. I’d like to end the section regarding Faridah Ali’s 2003 criminal cases with a quote that only those with a sense of Black Mafia history can truly appreciate (and I am not arguing all of the corruption to which they pleaded guilty, or of which they were convicted, is less important). During the proceedings, an Assistant U.S. Attorney told the court, “Shamsud-din Ali and Faridah Ali had a practice in the enterprise to regularly collect money from drug dealers for themselves.” Faridah was sentenced to 24 months in federal prison, and was released in March 2009.

By now, you may be asking yourself, “How do people with such notorious histories keep getting government contracts – and having such influence – in one of the largest cities in the U.S.? (please also see note 3 below)

Just as the late (then-City Councilman) Tom Foglietta and the late (then-Assistant District Attorney-turned-Judge) Paul Dandridge greatly assisted early Black Mafia efforts (their respective levels of knowledge about who they were assisting were always hotly debated), plenty of Philadelphia politicians over the years have knowingly or not lent legitimacy to folks like Shamsud-din and Faridah Ali. Do public officials know about their criminogenic activities and histories when they write letters of support for various initiatives? Or when they make connections for them? Or when they simply attend events with them (which can be exploited for many purposes)? Are they aware of how these ostensibly beneficent activities can be weaponized on the street? We will never know, and it certainly doesn’t help that Philly has been a one-party town for decades with such tight-knit, longstanding cliques of influencers. And as you know from above, Bob Brady is The Man in town.

During the spring of 2001, Bob Brady joined fellow U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah and Mayor Street in celebrating the anniversary of Shamsud-din Ali’s Sister Clara Muhammad School. Though the School had a certain public image, it was always the subject of street rumor and law enforcement intelligence spanning decades vis-à-vis drug proceeds being funneled into/through it. According to FBI agents who worked the Black Mafia cases, informants feared testifying against Shamsud-din because of his influence in the prison system. Brady and his colleagues were likely unaware of the vast narcotics probe well underway involving Shamsud-din Ali’s continued shakedowns of drug dealers. The drug probe ultimately resulted in authorities getting wiretaps approved for Ali’s phones weeks after the event attended by Brady, and the damning conversations which led to all sorts of powerful spheres in the city were overheard in the months that followed (as noted above, the drug and municipal corruption probes resulted in the guilty pleas or convictions, collectively, of 57 people).

Shortly before the corruption probe became public in Fall 2003, Faridah Ali submitted a $5.7 million proposal to the School District of Philadelphia for her Liberty Academy Charter School. Faridah was listed as president, while her daughter, Lakiha “Kiki” Spicer Ali, was vice president and Faridah’s son, Azeem Spicer Ali, was secretary. Among those who wrote letters of support of the school was U.S. Rep. Bob Brady.6

Beyond Bob Brady’s repeated and public support of Shamsud-din and Faridah Ali, he played a key role manipulating public opinion of the 2003 municipal corruption probe involving Shamsud-din and many others.

When the scandal exploded in October 2003 and became national news, numerous prominent local and national officials framed the probe as racist and/or an effort by the George W. Bush Justice Department to influence the looming November Mayoral election. They further argued the Bush Administration was hoping to flip Philadelphia for the Republican candidate in order to assist Bush’s re-election bid in Pennsylvania the following year. For example,

Bob Brady, the Philadelphia Democratic Party Chairman, joined with two other local Democratic congressmen and wrote a letter to Attorney General John Ashcroft and FBI head Robert S. Mueller soon after the bug’s discovery that stated, “The conduct of your personnel raises suspicions that this might be an attempt to intervene in and even compromise an election.”

Months after the November 2003 elections (Mayor John Street was re-elected), and after the many indictments stemming from the burgeoning federal corruption probe, Brady told a reporter he simply seized on a grand political opportunity during a close campaign when he made the damning allegations: “I was just spinning the shit, and it worked.”

spg

***

1. Earlier in Tom Foglietta’s political career, when he was a Philadelphia City Councilman, he publicly supported Black Mafia front “community development” organizations, including Black Brothers, Inc. Indeed, beyond assisting with incorporation documents and the like, Foglietta attended the grand opening of Black Brothers Inc’s South Philadelphia headquarters in the summer of 1973. Each of the five Black Brothers/Black Mafia leaders pictured by the Philadelphia Daily News at the event ultimately wound up in prison and/or murdered.

2. Philadelphia’s Black Mafia ended as a functioning syndicate following a large federal prosecution in 1984-85 (this was the second such case against its leadership; a similar 1973-74 case took the first generation of Black Mafia leaders off the street). Black Mafia alums and their offspring remained active in the underworld and in political life post-1985, but their days of dominating rackets in entire sections of the city were over.

3. Shamsud-din Ali was not alone when it came to Black Mafia leaders transitioning into “get-out-the-vote” campaigns and government contracting. Eugene Hearn, an officer in Black Brothers, Inc., was among the Black Mafia leaders sentenced in a massive 1973-74 federal drug racketeering case. Though not charged in the 1972 Club Harlem slayings mentioned above, Hearn was arrested among the Black Mafia crew fleeing the scene. Not long after his release from prison in the 1980s, Hearn (aka Fareed Ahmed) was overheard on FBI drug wiretaps speaking with Black Mafia head Lonnie Dawson. Dawson was convicted on numerous drug-related charges in 1982 for engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise. The case was the first joint FBI-DEA drug probe in the Philadelphia area, and then-Associate Attorney General of the United States Rudy Giuliani stated it was, “a perfect example of what can be accomplished by cooperation” between the agencies. Despite his significant involvement with Dawson, Hearn was not charged. Around this time, Hearn became the subject of media scrutiny when his campaign role for Mayor Wilson Goode garnered attention. It was also learned he received city funds for a community agency he founded. Politicians successfully avoided the issue by claiming they were unaware he was Gene Hearn of Black Mafia infamy; they claimed to only know him as Fareed Ahmed. Hearn/Ahmed was the source of FBI interest in the early 2000s during their probe of municipal corruption over government contracting, but neither he nor his businesses were officially implicated in wrongdoing.

4. Dawud Bey pleaded guilty in 2005 to distributing kilos of cocaine. Before he pleaded guilty on the drug charges, Bey was incarcerated along with his drug dealing partner Kaboni Savage in the federal detention center in Philadelphia. Like Savage, Bey was recorded threatening numerous people, ranging from witnesses to prison officials to family members of co-defendants he feared may testify against him. Bey later pleaded guilty to witness tampering for his “multiple attempts to threaten, intimidate, and coerce witnesses into refusing to testify in federal court.” He was collectively sentenced in the cases to eleven-and-a-half years in prison, served his time, and was released in February 2015. Bey’s co-conspirator Savage is his own frightening story.

Savage was convicted of federal gun, drug, witness intimidation and money laundering charges in December 2005 for leading a multi-million dollar drug distribution network that brought hundreds of kilos of cocaine into the city. He was later convicted for murdering twelve people, including a family of six killed in a 2004 firebombing (among them were a fifteen-month-old baby and three other children). The victims in the arson were relatives (including the mother) of a former Savage ally he suspected was informing against him. Savage was recorded mocking the victims saying his former partner should have brought barbecue sauce to his mother’s funeral. Such circumstances led the Philadelphia Daily News to title an article, “For Savage, the name fits”.

Kaboni Savage was sentenced to death in 2014, and a federal appeals court affirmed his death sentence in August 2020. Savage is the lone Pennsylvanian on federal death row.

5. Kiki Spicer (after dating a RAM Squad member and drug dealer named Tommy Hill – birth name John Wilson – who was later killed in 2011 when it was disclosed he had cooperated with authorities) went on to marry boxing great Mike Tyson. She met Tyson when she was eighteen years old because of Shamsud-din Ali’s relationship with promoter Don King and thus she often attended boxing events. Despite King’s much-publicized warning to “stay away” from her and from “these people” (i.e., Shamsud-din’s crowd), Kiki, who discovered she was pregnant with Tyson’s child a week before she entered federal prison in April 2008 (she was released on October 30, 2008), wedded Tyson in 2009 and the couple have two children together.

6. The highly-publicized federal corruption investigation and other probes into the Alis could not have helped the Liberty Academy proposal, which was rejected in April 2004.

Unless noted otherwise, all of the above is from Sean Patrick Griffin, Black Brothers, Inc: The Violent Rise and Fall of Philadelphia’s Black Mafia (Milo, 2005/07).